Most Agile teams use Jira as the backbone of their delivery process. User stories, epics, sprints, and releases all live there. Behaviour-Driven Development (BDD), however, often does not.

In theory, BDD fits naturally with Agile ways of working. In practice, teams frequently struggle to apply BDD consistently once delivery moves beyond a small, co-located team. This article looks at how Agile teams typically practise BDD in Jira today, where it commonly breaks down, and why those problems become more pronounced at scale.

How Agile Teams Typically Practise BDD in Jira

In many organisations, BDD is adopted with good intentions but limited structure.

A common setup looks like this:

-

User stories and acceptance criteria are written in Jira

-

BDD scenarios are discussed during refinement or sprint planning

-

Scenarios are written separately, often as feature files

-

Automated tests are executed through a CI pipeline

-

Test results are viewed outside Jira

At a small scale, this can work reasonably well. Teams communicate informally, and knowledge is shared verbally. As delivery grows more complex, the gaps start to show.

Where BDD Starts to Break Down

The most common problems are not technical — they are organisational and structural.

Visibility for non-technical stakeholders

BDD scenarios are meant to be readable by everyone involved in delivery. In reality, once scenarios live outside Jira, product owners and stakeholders lose visibility. Behaviour becomes something that is implemented and tested, rather than something that is shared and agreed.

Weak traceability

When scenarios are not directly linked to Jira issues, it becomes difficult to answer basic questions:

-

Which behaviours have been validated?

-

Which user stories are covered by scenarios?

-

What has actually been tested in a given release?

Teams often rely on assumptions rather than evidence.

Scenario sprawl

As projects grow, so does the number of scenarios. Without structure, teams struggle to manage duplication, ownership, and consistency. Scenarios become harder to maintain, and confidence in them drops.

Reporting gaps

Automated test results may exist, but they are often disconnected from the stories and behaviours they relate to. This makes it difficult for delivery leads and product owners to understand quality in meaningful terms.

The Role of Cucumber — and Its Limits

Cucumber is widely used to execute BDD scenarios written in Gherkin. It does its job well: validating behaviour through automated tests.

However, Cucumber focuses on execution. It does not solve problems around:

-

Managing scenarios as delivery artefacts

-

Making behaviour visible to non-technical roles

-

Maintaining traceability in Jira

-

Reporting on behaviour in a way stakeholders understand

These are not shortcomings of the tool; they are simply outside its scope. Problems arise when teams expect execution tools to solve collaboration and visibility challenges.

Why These Issues Get Worse at Scale

Many teams find that BDD works well initially, then becomes harder to sustain.

As organisations scale:

-

More teams contribute scenarios

-

More projects share similar behaviours

-

More releases depend on understanding what has been validated

Without a clear way to manage behaviour alongside delivery, BDD artefacts become fragmented. Teams lose confidence in scenarios, and BDD gradually becomes “something testers look after” rather than a shared practice.

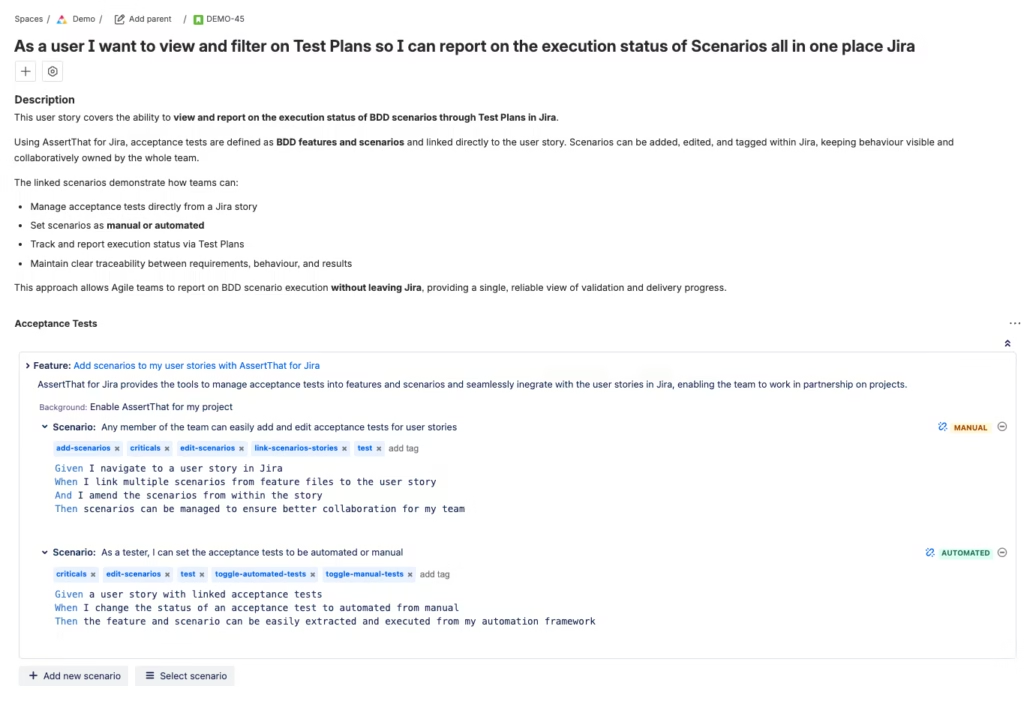

What Effective BDD in Jira Looks Like

Agile teams that succeed with BDD treat behaviour as a first-class delivery concern.

In practice, this means:

-

Behaviour is visible within Jira, not hidden elsewhere

-

Scenarios are clearly linked to user stories and requirements

-

Both manual and automated validation are supported

-

Stakeholders can see what behaviour has been covered and tested

-

Reporting reflects behaviour, not just test execution

When this structure is in place, BDD supports collaboration rather than adding overhead.

Final Thoughts

BDD does not fail in Jira because the methodology is flawed. It fails when behaviour is managed outside the tools where delivery decisions are made.

Understanding where these gaps appear is the first step. Addressing them requires treating behaviour as part of the delivery workflow, not an afterthought.